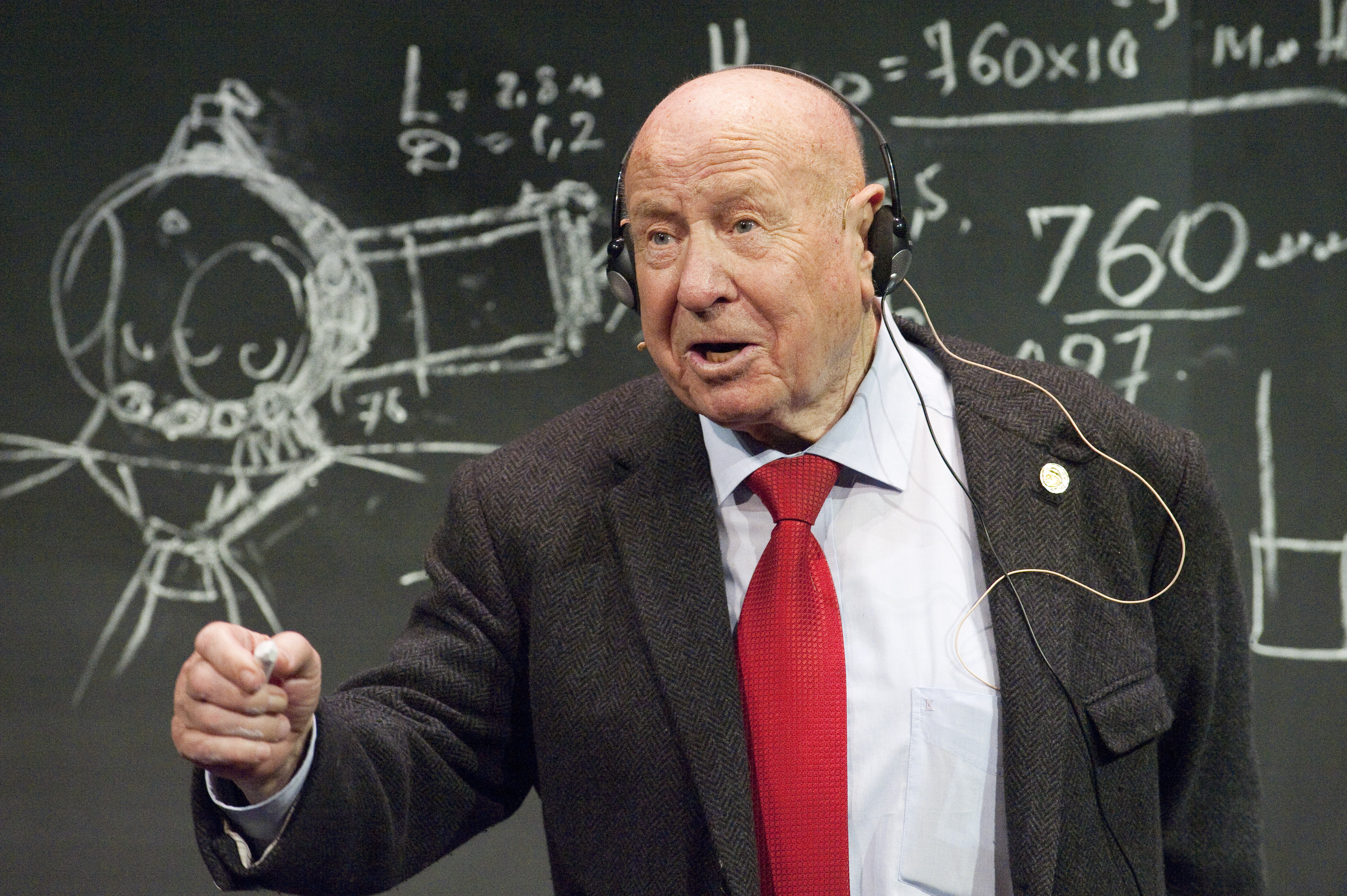

With the help of chalk and blackboard, Alexei Leonov recently gave a vivid personal account of the first seventy years of practical cosmonautics, from the birthplace of modern rocket science in Nazi Germany to his first ‘step into the abyss’ and the prospect of asteroid apocalypse.

At an event organised by the Starmus Festival, Leonov was introduced to a celebrity-laden audience in the museum’s IMAX theatre by Director, Ian Blatchford. Earlier that same day Blatchford and Leonov had sat in front of a reproduction of Leonov’s painting of his pioneering spacewalk to announce the most ambitious exhibition in the history of the Museum, Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age, supported by BP, when many Soviet spacecraft will be gathered together for the first time.

As Mr Blatchford thanked the twice-hero of the Soviet Union, whose character is every bit as bold as his space feats, Sputnik 3, Soyuz and a Lunokhod 2 rover were being lifted through the museum into their temporary home on the first floor. Vostok 6 and Voskhod 1 had arrived the day before, the first wave of around 150 iconic objects that hail from the dawn of space exploration.

Leonov began by recounting Nazi Germany’s attempt ‘to destroy London’ in the Second World War, when modern rocketry was launched with the V-2, the first long-range guided ballistic missile. When the Russian Army entered Peenemünde, among them an expert group including Sergei Korolev, who would come to be known as ‘The Chief Designer’ in the Soviet Union), the Germans had left only 10 minutes earlier. ‘The coffee was still warm’, said Leonov.

The German rocketeers who had already fled included Wernher von Braun, who would become the father of the US Apollo moon programme, and had by then surrendered to the Americans in Austria. Von Braun had wanted to defect to the Americans but later told Leonov that he would have worked for the Soviets too, claiming he wanted to use rocketry for exploration, not murder. ‘He was very sincere, very frank,’ said Leonov, ‘though you may chose not to believe his words because these were weapons, after all.’

The USSR captured a number of V-2s, including one from the marshes of Peenemünde, and German staff. This paved the way for the manufacture of a Soviet duplicate, the R-1. By August 1957, a descendant, the R-7, was capable of launching a satellite into orbit.

The space age dawned with the launch of Sputnik 1, which was ‘just a sphere with a transmitter…beep beep, beep beep,’ said Leonov. ‘That was sufficient for people to get very excited, now we are in an era where there is an artificial object floating in space. This was only the beginning.’

The Soviet Union followed Sputnik by launching the first animal, man and woman into orbit in just six years, feats that will be recorded by the Science Museum’s Cosmonauts exhibition with objects ranging from a dog ejector seat from a sub-orbital rocket to a model of Vostok 1 (Russian for ‘East’), which carried Yuri Gagarin into space, and Valentina Tereshkova’s Vostok-6 descent module.

After chalking the outline of a Vostok, Leonov moved on to the Voskhod (Russian for “sunrise”), which he said was part of a lunar programme that began with a directive in 1962 and was officially sanctioned by the Politburo two years later.

Voskhod 1 launched on October 12, 1964. Even though there was not enough room to wear space suits, or time to develop a launch escape system, it successfully took the first three-man crew into orbit years before the US Apollo’s three-man crews.

Voskhod 2 featured more powerful propulsion, TV and had been adapted to allow Leonov to carry out the first ever spacewalk. The spacecraft carried a ‘genius invention’, he said, an airlock that could be inflated through which a cosmonaut could step into open space. ‘That was me,’ said Leonov.

Earlier, Korolev had told him, ‘as a sailor should know how to swim in open ocean, so a cosmonaut should be able to swim in space.’

But Leonov’s ill-fated mission almost did not take place. An earlier automated unmanned test flight – Voskhod 3KD – had been destroyed after ground controllers sent a sequence of commands that accidentally set off a self-destruct mechanism designed to prevent the craft ending up in enemy hands.

At a meeting in a hotel, Korolev told Leonov he hoped to adapt his Voskhod 2 to complete the unmanned mission to test the airlock and spacesuit. ‘We were set dead against it,’ said Leonov. He protested to The Chief Designer: ‘We have personally worked through 3000 emergency scenarios’, which was greeted, understandably, with scepticism. ‘Yeah, of course you did,’ said Korolev. ‘You are sure to come across the three thousand and first. And, of course, Leonov ‘would know what to do.’

Leonov admitted to the audience that Korolev’s cynicism was well placed. To carry out his spacewalk above the Black Sea, on 18 March 1965, he and his crewmate Pavel Belyayev came across the ‘three thousandth and second and third and fifth and sixth…all of them were not described in any instructions before.’

As Leonov ‘stepped into the abyss’, he was struck by the sound of his own breathing, his heartbeat and a sense of the universe ‘being limitless in time and space’. Given that in the darkness the temperatures plunged to minus 140 deg C and in sunlight rose to 150 deg C his suit was ‘a stroke of genius’ for the way it kept him at a comfortable 20 deg C.

But eight minutes into the spacewalk, he felt that his gloves had expanded so much that he could no longer feel them with his fingers any more. His legs started to shake. Leonov’s spacesuit had by now ballooned in space to an alarming degree. ‘I started feverishly thinking of what I was going to do to re-enter the spacecraft’.

First he had to coil his tether. Every 50 cm dangled a 2.5 cm diameter ring, which he was supposed to hook.’ But he had ‘no support’ and was hanging on by one hand. ‘It was very hard.’

He disobeyed the orders of Korolev – there was no time to wait for a committee to be assembled to deliberate on his predicament – and opened a valve to bleed of some of the suit’s pressure, risking the bends by lowering the pressure beyond the safety limit.

On his back Leonov wore ‘metal tanks with ninety minutes’ worth of oxygen’ but it was clear from his talk that he remained concerned he had not left enough time for the nitrogen from the oxygen/nitrogen mix inside Voskhod to be purged from his blood. ‘There was a danger of nitrogen boiling in my blood and I was feeling this needling sensation in my fingers but I had no choice.’ Fortunately, ‘The feeling went away.’

Instead of entering legs first, as he had trained to do, Leonov went in head first, requiring ‘an awful amount of energy’ to turn around in the confines of the 1.2 m diameter airlock (he measured 1.9 m in his spacesuit). His core body temperature soared by 1.8 °C as he contorted himself. ‘That was the most stressful moment.’ Overall, the spacewalk lasted 12 minutes. By that time, Soviet state radio and television had stopped their live broadcasts.

The mission’s problems were far from over. The descent module’s hatch failed to reseal properly, leading to a slow leak. The craft’s automated systems flooded the craft with oxygen, raising the risk of fire of the kind seen in the Apollo 1 tragedy.

When they turned on their automatic descent systems, the spacecraft did not stop rotating. ‘It was difficult and dangerous to stop.’ Their automatic guidance system had malfunctioned. They asked Korolev for permission to conduct a manual descent, which the craft was not designed to do. ‘It was very similar to driving a car looking out the window from the side.’ From an ‘ancient Soviet radio station’ in Antarctica came permission, along with a note of caution: ‘Be careful.’

‘You know what, let us land in the Red Square, it would be so jolly funny,’ remarked Leonov, who was the mission navigator. Belyayev, commander, replied that they would ‘clip all the stars in the Kremlin so I don’t think we should do it’. Eventually, Voskhod 2 ended up far from the primary landing zone on the steppes of Kazakhstan, in polar forests – taiga – around 180 kilometres from Perm in Siberia. ‘To us, the trees of 30-40 m looked like a manicured lawn.’ Leonov transmitted a call sign with a manual telegraph system – ‘everything is in order’ – but it was greeted by silence.

A gust of cold air entered when they opened the hatch. Belyayev jumped out and ended up neck deep in snow. Leonov was sloshing around knee deep in water in his spacesuit. They stripped in the cold and Leonov wrung out his underwear. ‘Can you imagine this picture – a spacecraft, the taiga, and naked chaps standing next to each other?’

The next day, ‘comrades on skis’ arrived and, after another night and a nine kilometre ski trip, they were picked up by helicopter.

The Soviets had originally planned to orbit the moon in 1967 and had two parallel lunar programmes, one manned and one unmanned (This was a mistake, Leonov conceded). On his blackboard, Leonov drew a Soyuz (Russian for ‘Union’) 7K-L1 ‘Zond’ (‘probe’) spacecraft that was designed to circle the Moon and described how he had even studied the sky in Somalia to decide which stars to use for lunar navigation. ‘Everything was ready.’

Leonov was once the Soviet cosmonaut thought most likely to become the first human on the Moon. But the Soviet lunar programme was starved of resources compared with America’s Apollo programme, the Soviet manned moon-flyby missions lost political momentum and Korolev died in 1966 (‘those who took his place decided this was too risky’). One could sense his frustration when he declared: ‘Six spacecraft orbited the moon without a man on board.’

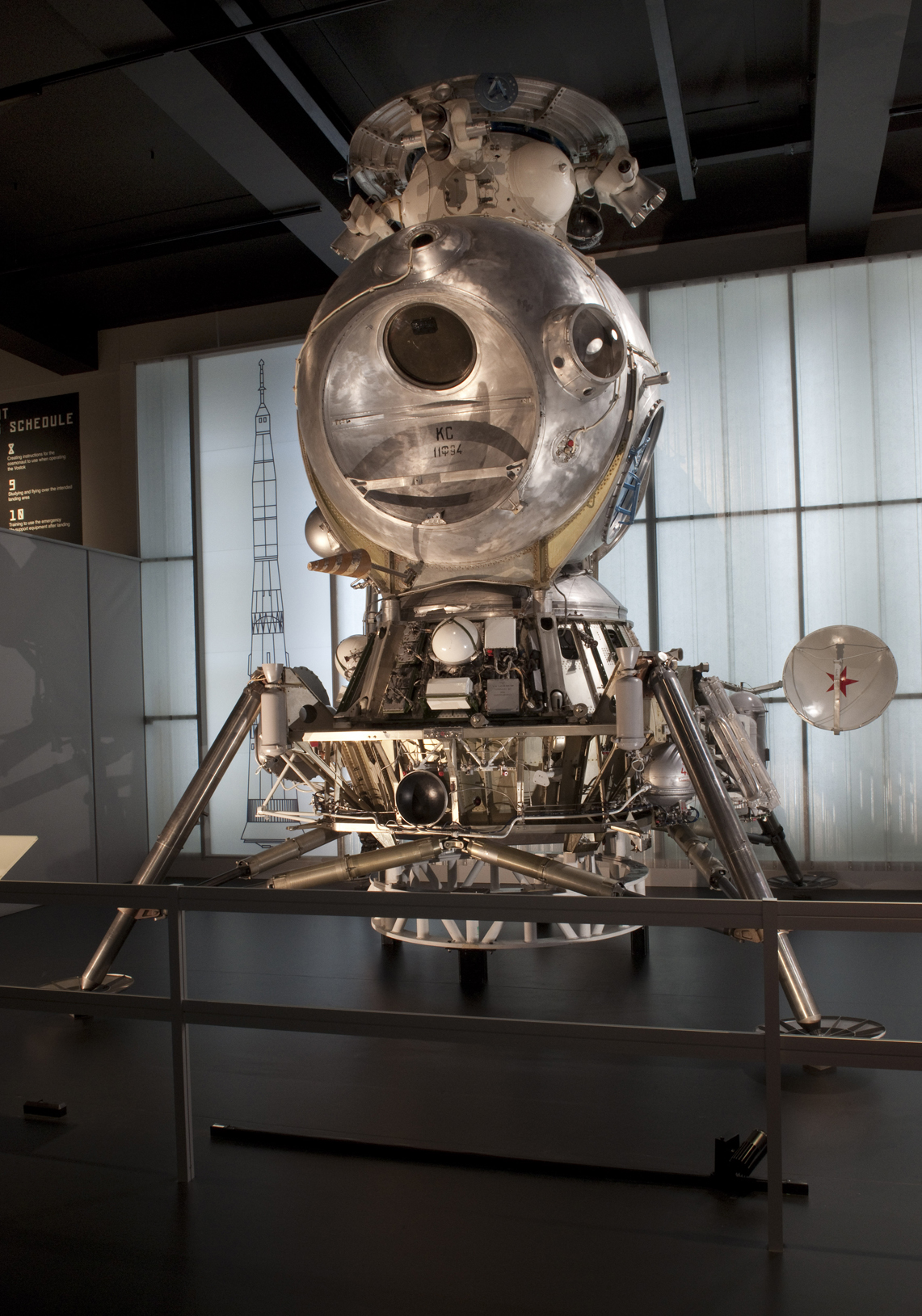

However, Science Museum visitors will be able to inspect the monumental five metre LK-3 lunar lander, the finest example of its kind, which was designed to take a single cosmonaut to the Moon’s surface.

Leonov counted himself lucky to be part of the Apollo Soyuz mission, when ‘the cold war could become a hot war at any moment.’ Conducted in July 1975, it was the first joint US–Soviet space flight, and the last flight of an Apollo spacecraft. The mission was a symbol of superpower détente. ‘Every day we spoke on Good Morning America,’ said Leonov. He groaned with mock horror, ‘awwww’, acting out the apoplexy of small-town America at the thought of a cosmonaut orbiting overhead.

Leonov went on to talk about how singer Sarah Brightman had cancelled her trip to the International Space Station, mention the Soviet Buran shuttle, which was delayed by discussions about pilots and automated control (the latter won but ‘we lost three years, launched only one and then nobody commissioned it’) and discussions to allow China to dock with the ISS.

He also discussed the greatest threat to humanity, that of asteroid impacts (now marked by Asteroid Day), which demanded the best of human ingenuity and technology in response. In 2008 the Association of Space Explorer’s Committee on Near-Earth Objects and its international Panel on Asteroid Threat Mitigation gave recommendations to the United Nations. ‘So far we have not heard back from them. I think they are waiting for the asteroid to hit them’.

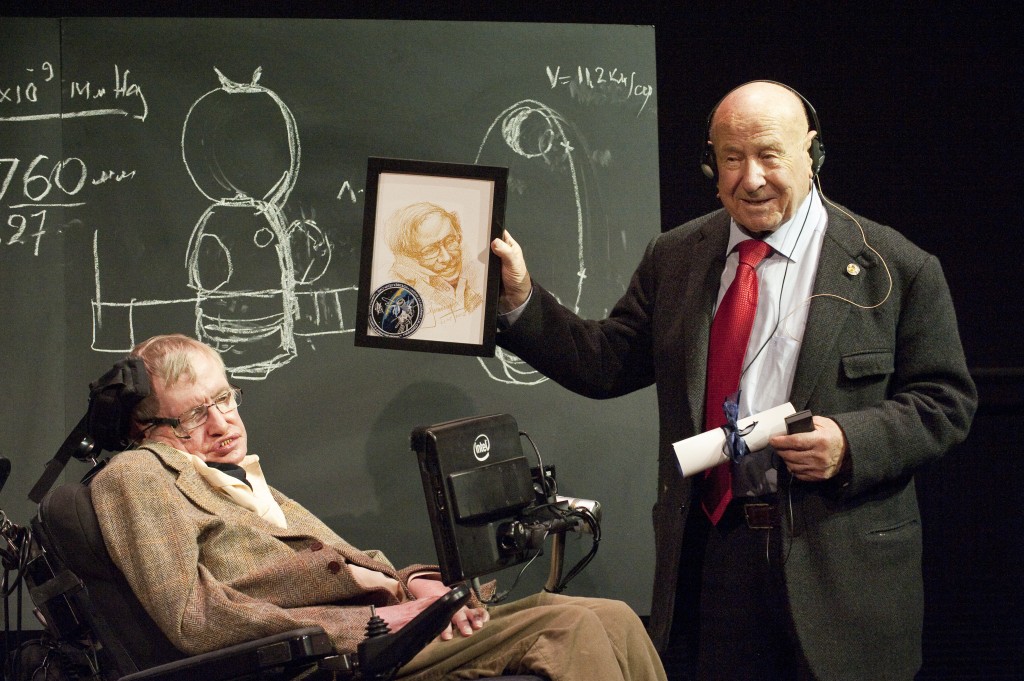

Leonov had before him in the Science Museum IMAX an audience that ranged from amateur space enthusiasts to rock legends Brian May and Rick Wakeman, and the world’s best known scientist, Professor Stephen Hawking, who had recently given a highly publicised tour of the Science Museum. Leonov described him as ‘amazingly courageous’.

Sitting in the front row of the IMAX was the UK’s first astronaut, Helen Sharman, whose Sokol space suit will be shown in Cosmonauts. Leonov described how he had a ‘very moving’ reunion in the museum with ‘little Helen.’ ‘The best pupil I have ever had,’ said Leonov.

Sharman had been selected to travel into space on 25 November 1989 ahead of nearly 13,000 other applicants. She blasted off in 1991. Leonov encouraged her to stand, and the audience showed their appreciation with a round of applause. ‘She had a special energy, special intellect. You should be proud of this person.’

At the end of the event, Leonov was presented an honorary fellowship of the Science Museum by Hawking and the Chairman of the Board of Trustees, Dame Mary Archer. In return, Leonov, who had dined with Hawking earlier that day, presented the Cambridge cosmologist with a portrait he had sketched after lunch. ‘Stephen smiled, hooray,’ a delighted Leonov told the audience, who were also addressed by Alistair Scott, President of the British Interplanetary Society, and astronomer Garik Israelian of the Starmus Festival.

At a celebratory dinner in the museum that night, Leonov gave a speech in Russian (he preferred his mother tongue because, as he cheerfully recounted, he once ended a speech given in English by wishing his audience ‘sex for life’ rather than ‘a successful life.’) Leonov also alluded to the prevailing American bias in museum accounts of space history. He praised the Science Museum for containing the ‘wisdom of the world’ that would be an ‘inspiration and lesson for future generations.’

Roger Highfield, Director of External Affairs, spent a day with the pioneering cosmonaut for the launch of Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age.